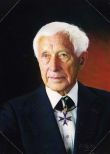

(March 29th 1895 to February 17th 1998)

Translated by Christoph Werner (Weimar, Thuringia) and Michael Leonard (Petaluma, California)

Thomas Mann called Ernst Jünger, who was the only 20th century writer equal to him in mastery of style, "an ice-cold apostle of barbarism". “Meyers Neues Lexikon" published in East Germany in 1962 states that Jünger was an ideological precursor to German fascism, and through his works published in West Germany "has become a prominent representative of the militarist and neo-fascist literature. Because he has cloaked his ideas in a philosophical garment and written in a brilliant style, he is a particularly dangerous enemy of political progress."

Arno Schmidt, who Jünger called "the Diderot from Lower Saxony", had little respect for him.

We, who grew up in communist East Germany, had no access to Ernst Jünger's books; what we could read of him we either found in the libraries of our fathers (as this author found Jünger's book "Auf den Marmorklippen" (On the Marble Cliffs)) or got illegally from West Germany (as this author got hold of Jünger's "In Stahlgewittern" (The Storm of Steel).

It seems that anybody who utters an opinion about Ernst Jünger is not quite wrong, and the secondary literature on him contains contradictory assessments. Almost no other important artist reached his age of 103 years, a span that can only be called biblical.

At 18 years old Jünger joined the French Foreign Legion, though his father had him brought back to Germany because of his youth. It seems that he could not wait to pursue his ideal of manhood, which he felt was embodied mainly in the military.

Already on August 1, 1914, just four days after the outbreak of World War I, he volunteered for the army and fought (incidentally in the same regiment as Hermann Löns, who died in combat on September 26th, 1914) up to the end of the war – from 1915 onward as a lieutenant – on the Western Front and was wounded at least seven times.

Conspicuous for his bravery, he was awarded the Pour le Mérite medal, Germany's (originally Prussia's) highest military decoration, in 1918.

During the war he kept a diary, which was to become the basis for his book "In Stahlgewittern" (The Storm of Steel) (1920).

The book contains vivid recollections of his life in the trenches and his experiences in combat as a company commander.

Today's reader will find it hard to accept the dispassionate matter-of-fact way in which the writer describes death and destruction as unfortunate consequences of war.

The realistic narratives of the deaths of uninvolved French civilians or the successful killing of enemy soldiers are followed by casual descriptions of the German soldiers getting together in comradeship for good meals, drinking, smoking and the telling of dirty jokes.

The bloody side of the war is made clear but portrayed at the same time as the unavoidable cost of the battles being fought for the continued existence and aggrandizement of the fatherland, and thus no regrets are uttered or morally required.

"In Stahlgewittern" became an eventual success in Germany and other countries.

After his discharge from the army Jünger studied zoology and philosophy at Leipzig and Naples from 1923 to 1926, though without completing his studies.

Despite his militarism, his preference for authoritarian government and his radical nationalist ideals, Jünger resisted all invitations by the Nazis to join their movement.

Adolf Hitler would certainly have liked to win the war hero to his party.

Instead Jünger wrote a daring allegory on the barbarian devastation of a peaceful land, "Auf den Marmorklippen" (On the Marble cliffs) (1939), which surprisingly passed the censors and was published in Germany.

There was a rumor, hard to believe, that his publisher, avoiding the censorship authorities, quickly supplied the book to the bookshops without official permission.

It was said that Hitler personally forbade molesting the recipient of the Pour le Mérite, whose war books he admired.

Shortly after the start of World War II Jünger again volunteered for the army with the wish to fight at the front. He was admitted and promoted to the rank of captain.

In 1941 he joined the staff of German-occupied France's military commander, where, among other things, he was responsible for the censorship of the correspondence of the soldiers. According to his own words he denounced soldiers who for example illicitly sold a pound of coffee; but if someone wrote that Hitler deserved to be hanged he made the letter disappear (Interview with "Der Spiegel" magazine from 1982).

He was indirectly implicated in the 20th July plot to kill Hitler, though miraculously, as one biographer noted, escaped arrest, and was instead discharged from the army.

A few months later, his son died in combat in Italy after having been sentenced to a penal battalion for speaking derisively about Hitler.

A few months later, his son died in combat in Italy after having been sentenced to a penal battalion for speaking derisively about Hitler.

After the war, until 1949 Jünger, was banned from publishing his works because he was said to be a forerunner of National Socialism.

Later he travelled and continued to write until shortly before his death. In 1986 he went to Kuala Lumpur in order to see Halley's Comet for the second time in his life.

Besides many other awards he received the Goethe Prize from the city of Frankfurt despite loud protests by the Green Party in the city parliament.

On July 20th, 1993 the French president Mitterand and the German chancellor Kohl, as a sign of honor, visited Ernst Jünger in his house in Wilflingen (Upper Swabia).

In 1996 Jünger converted to catholicism, which only became known after his death.

Reading Jünger's books leaves one with conflicting impressions.

On one side is the unquestionable evidence of his personal integrity and bravery, which made him demand from others only what he was prepared to give himself.

On the other side there is the question of how far, if at all, he realized that art and conscience belong together.

It can hardly be denied that his brilliant style, the mastery with which he made use of the German language and the fascination he himself aroused as a person contributed to something tragic, namely to the enthusiasm of young men for war as a heroic form of life, which finally led to their deaths on the battlefields of the Second World War.

This article does not deal with the numerous works by Jünger, among which his socio-political and futuristic designs would deserve a closer look.

Instead, this author would like to draw your attention to one of the most outstanding literary works of the 20th century, "Auf den Marmorklippen", despite its unspecified era and uncertain scenery, a composition of mediterranian and Alemannic landscapes.

In the struggle between the obscure forces from the woodlands and bogs, personified by the "Oberförster", a figure of a horrid joviality, virtually a second Göring, and his zombie-like followers, and the forces of Campagna and Marina, who stand for tradition and culture, the Oberförster gets the upper hand, which Jünger describes in phantasmagoric and bloody scenes.

And yet, the reader is left with the hope that the victory of the Oberförster is not final, that the power of the pure mind and the force of subtle language, in which the indestructible culture finds its expression, will prevail.

Ernst Jünger. 1939/1941. Auf den Marmorklippen. Hamburg-Wandsbeck. Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt Aktiengesellschaft.

This article does not deal with the numerous works by Jünger, among which his socio-political and futuristic designs would deserve a closer look.

Instead, this author would like to draw your attention to one of the most outstanding literary works of the 20th century, "Auf den Marmorklippen", despite its unspecified era and uncertain scenery, a composition of mediterranian and Alemannic landscapes.

In the struggle between the obscure forces from the woodlands and bogs, personified by the "Oberförster", a figure of a horrid joviality, virtually a second Göring, and his zombie-like followers, and the forces of Campagna and Marina, who stand for tradition and culture, the Oberförster gets the upper hand, which Jünger describes in phantasmagoric and bloody scenes.

And yet, the reader is left

with the hope that the victory of the Oberförster is not final, that the

power of the pure mind and the force of subtle language, in which the

indestructible culture finds its expression, will prevail.

Ernst Jünger. 1939/1941. Auf den Marmorklippen. Hamburg-Wandsbeck. Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt Aktiengesellschaft.

*****

Ernst Jünger in 1921. Source: Book of Ernst Jünger: In Stahlgewittern, Berlin 1922, 3rd edition, in the public domain

Ernst Jünger. Foto: Ilse Jäger

Conference room after the explosion. Federal Archives, Picture 146-1972-025-12 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

The President of the German Bundestag, Dr. Philipp Jenninger, receives the author Ernst Jünger in his office e in Bad Godesberg. Bundesarchiv, B 145 Picture / F073370-0003 / Wegmann, Ludwig / CC-BY-SA 3.0 on the Wikimedia Commons

Tomb of Ernst Jünger. Foto: Ilse Jäger

![Ernst Jünger [en] Ernst Jünger [en]](/index.php?rex_media_type=contentBild&rex_media_file=ernst_juenger_insg.jpg)